Aleksander Laskowski

Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences

Adam Mickiewicz Institute

Dariusz Przybylski. A courageous passéiste

Abstract

Dariusz Przybylski is a prolific composer and organist. His output includes a number of operas, sacred works and various instrumental forms, both chamber and orchestral. Aleksander Laskowski analyses Przybylski’s aesthetic choices and his position in the world of contemporary music, describing him as a ‘courageous passéiste’. The analysis calls upon the methodology developed by the French sociologist Nathalie Heinich for contemporary art, whereby a set of criteria are used to distinguish between contemporary, modern and classic art. Przybylski, an unrelenting non-contemporarian, is seen through the prism of general music criticism as well as essays of Krzysztof Lipka, who is an ardent propagator of his music.

Key words

passéism, contemporary music, new music, opera, sacred music, contemporary art

Dariusz Przybylski is a composer and organist. Born in 1984, he is prolific and versatile, his output is considerable in the number of compositions and staggering in the variety of form. Przybylski counts among his composition teachers Marcin Błażewicz, York Höller, Krzysztof Meyer and Wolfgand Rihm. Perhaps one could call his output Rihmian in the sense that it spans different genres and musical forms and draws on a seemingly unlimited number of sources of stylistic or aesthetic inspiration. Przybylski also seems to share with Wolfgang Rihm a similar approach to the role and function of ‘New Music’. Also its very place in society:

ZEIT: Welche Räume braucht die sogenannte Neue Musik?

Rihm: Jedenfalls braucht sie keine, in denen sie als ‘sogenannte Neue Musik’ unter Verschluss gehalten wird.1 (Rihm, 2016)

Wolfgang Rihm has been called an Olympian of contemporary music (cf. Büning, 2013). He chiselled the musical thinking to the extent that he is no longer considered a Nischenphänomen – a composer belonging to the niche of New Music. And his output spans many genres – from orchestral pieces through operas, chamber and solo music, both vocal and instrumental, as well as film music. His music belongs in the subscription concert halls and major festivals more than in contemporary music festivals. This cannot yet be said about Dariusz Przybylski. However, his work seems to be heading in the same direction. For a relatively young composer today to be so form-oriented, even sound-oriented as Przybylski, is a brave aesthetic stance in the times when the received notion that music must be sound is called into question, as in Barrett’s recent book (2016):

It might come as a surprise, but the very notion of music as sound is a relatively recent invention. With its roots in the writings of a group of German thinkers in the early 1800s, the equating of music with instrumental sound severed from language and social meaning, which was later termed ‘absolute music’, has remained with us to this day. […] Absolute music, further sedimented in the mid-nineteenth-century musical aesthetics of Eduard Hanslick – particularly his notion of the ‘specifically musical’ (as opposed to the extra-musical) – would undergo its most exhaustive sequence in the music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, expanding to include electronic sound recording technologies among other formal and technological innovations. This music stretches from Beethoven to Boulez, but also includes Ruth Crawford Seeger, Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen, worked through the same artistic modernisms that brought us expressionism and the subsequent debates about medium specificity in the visual arts. […] Beginning in the 1960s, conceptual art would initiate a dismantling of medium specificity that extends to recent debates around the ‘postmedium condition’ and beyond. (pp. 1–2)

Barrett (2016) further claims that we live in an era of

the decline of Western art music to the point of critical paralysis in the face of global crisis. Amid the twin threats of global economic and environmental collapse, a profound silence has befallen music and its institutions. Music has steadily developed from its status as one of the most culturally relevant and aesthetically radical art forms – playing a decisive, if not foundational role in the development of movements such as conceptual art, Fluxus, performance, intermedia, site specificity, and social practice – to an unprecedented level of cultural conservatism, political impertinence, and artistic regress. With few exceptions, (new) music has become the last place to listen for new forms of engagement. (p. 7)

A possible way of finding space (or a logical possibility of the very existence of) for a composer like Przybylski – or Rihm or the late style of Krzysztof Penderecki – would be to adapt for music Nathalie Heinich’s way of thinking about classic and contemporary art. Nathalie Heinich in her widely debated article (1999) suggested that one should treat contemporary art as a separate genre, different from modern and classic art. In this article Heinich ponders on the specificity of contemporary art, including the ontological borders, which define the limits of this concept. The ideas proposed in the said article are further developed in her book (Heinich, 2014). One could find a number of analogies between contemporary art as opposed to modern and classic art and contemporary music discussed in the context of the so-called classical music, therefore it seems that Heinich’s tenets and postulates are worth closer investigation, as they may be used as a point of reference in the study of works of such a composer as Dariusz Przybylski.

Here is how Heinich presents the traits of contemporary art understood as a new paradigm:

The importance of discourse (description, narrative, interpretation), the primary role of specialists in the position of intermediaries between the works of art and the public, the necessity of the artist to be present to access the work of art; diversification of materials, the disappearance of framed painting and sculpture on pedestal, often unsatisfactory character of reproductions, the importance of the value of singularity, a play with the borderlines, credit given to any form of creating distance, the effacement of the criterion of beauty; close links between the actors of the private market (gallery owners, art collectors) and the actors of the public institutions (museum conservators, exhibition commissionaires, directors of arts centres); internationalisation of exchange, the shortening of the time necessary to gain recognition.2 (Heinich, 2014, p. 15)

The specific, even formative characteristic of contemporary art is that our perception of this art changes radically, depending on whether we belong or do not belong in this world cf. Heinich, 1999, p. 16:

[…] on the one hand the privilege accorded to originality rather than to respecting conventions; on the other hand the transfer of the point of reference, of the works of art to the person or attitude of the artist in such way that the work of singularisation done by the artists on their own becomes a pregnant part of their works, which is confirmed by the regularity of such efforts. This is all a culture of contemporary art which constructs itself and communicates itself in the narratives of eccentricity – and in anecdotes.3 (Heinich, 2014, pp. 18–19)

Heinich believes that to establish contemporary art ontologically three conditions need to be fulfilled, which concurrently leads to a discontinuation of habits of the history of art and of art criticism. The first condition is to consider the works of art collectively and not individually, with the assumption that they all share a common grammar; hence the need to analyse the relations between such works on the syntagmatic axis (to borrow a term from linguistics).

The second condition is that the works of art should be interpreted not in the context of the continuity of the past (through the study of cross-influences), but through the investigation of differences with the existing models – thus the paradigmatic axis of interpretation is created.

The third condition is that the imperative of discursive interpretation is suspended (with discursive interpretation often based on the assumed intentionality of the creator: ‘the artist wanted…’) and replaced by a description which takes into account various factors, a description based on observation and not speculation: description of the features of a given object (ontological approach), its effect or consequences (pragmatic approach) and universe, in which it functions (contextual approach).

To consider contemporary art no more as a chronological category (a certain period in the history of art) but as a generic category (a certain definition of artistic practices) to me seems to have the advantage of allowing a certain tolerance in this respect. Because even if we readily admit the right for various genres to exist simultaneously, even in a hierarchical order like in the classic painting (historic painting, portrait painting, landscape painting, etc.), still we have to tolerate, in our contemporary world, the simultaneous existence of contemporary and modern art, even the existence of classic art, although it does not have practitioners anymore (yet it has many followers).4 (Heinich, 2014, pp. 24–5)

Heinich (2014) supports her reasoning with an argument borrowed from the historian of art Thierry de Duve: ‘Une oeuvre d’art serait contemporaine – par opposition à moderne, anciennes, classique, tout ce que vous voudrez – tant qu’elle demeure exposée au risqué de n‘être pas perçue comme de l’art’ (p. 27). Heinich also cites the research of Bénédicte Martin5 who studied the contemporary art market but she adds her own comment:

[...] if we submit these results to a factor analysis of correspondences, distinguishing on the first axis ‘the manner in which we consider the works of art’ (‘production’ or ‘expression’), and on the other axis the principal values according to which we evaluate the works of art (‘uniqueness’ or ‘beauty’), we shall notice a marked difference between the class corresponding to contemporary art – where art is considered to be production and where the value of uniqueness is primordial – and the class corresponding to classic art – where art is considered to be a form of expression and where the principle of beauty reigns. As far as the class corresponding to modern art is concerned, it shares with one category the concept of art as a form of expression but privileges the uniqueness […] in the evaluation of works of art. One could not possibly better illustrate the situation of modern art, between classic art and contemporary art, not only in the chronological perspective but also in the light of the ontological definition of art, as well as in the light of the axiology of its evaluation.6 (Heinich, 2014, p. 33)

I believe that Heinich’s reflections can be also applied to music. The difference is, however, that classical music not only still has its amateurs but also practitioners. Dariusz Przybylski is one of them. It seems that today the ontological status of ‘new music’ is strong. It also seems that – when treated as a separate branch – ‘new music’ is closer to contemporary art and postdramatic theatre than to classical music as such – i.e. the presence of the creator/artist is a must and it favours uniqueness and singularity (one-offs), site-specific events, and a well-established distance to the very concept of beauty – Wojtek Blecharz’s Transcryptum or Park-Opera would be good examples here.7 It seems that treating ‘new music’ as a separate ontological category allows one to investigate the more traditional contemporary music with more freedom and without the abusive preconception that what does not fall in the ‘paradigm of progress’, falls out of history. The question remains, however, whether a given composer is worth investigating. I believe that Przybylski is. It is a belief apparently shared by Lipka (2015):

[…] Przybylski’s music is deeply rooted in musical tradition, and evidently refers to musical Romanticism, though without losing its contemporary character. It seems that the phenomenon of Przybylski’s style could be largely explained as a contemporary ‘sound-tissue’ constructed with an excellent knowledge of the past epochs, with highly stylized references to the best models – Romanticism, Baroque, and Impressionism. […] The boldness of expression is counterbalanced by a diligent refinement of every detail in this work. The author pays great attention even to the subtlest of details, which shape the finesse and refinement of his music. (p. 9)

Przybylski’s passéism manifests itself in a number of ways – through the choice of musical forms (e.g. chaconne, concerto), the relationship of music and text in his works (both lieder and operas), and even in the very titles of his compositions (e.g. Berceuse, Bagatellen, Konzertstück). Particular attention should be paid to his work in the field of sacred music, which include:

- Nisi Dominus for soprano and female choir, op. 2, 2002

- Laudate pueri for mixed choir a cappella, op. 6, 2003

- Bogurodzica (Mother of God) for the organ, op. 7, 2003

- Ave maris stella for mixed choir a cappella, op. 8, 2003

- Salve Regina for mixed choir a cappella op. 10, 2003

- Missa brevis for female choir and the organ, op. 19, 2005

- Cantata in honorem Sancti Bartholomaei for baritone, choir, brass and organ, op. 27, 2006

- Miserere for a vocal ensemble, op. 41, 2008

Przybylski courageously finds his way in the field of sacred Weltanschauungsmusik, in a world dominated by Krzysztof Penderecki, whose St Luke Passion earned him both the title of the Verräter der Avantgarde, the traitor of the avant-garde, and that of the “Last of the Mohicans” of Sacred Music. Przybylski holds a strong foothold in the same “Mohican reservation”, although his Passion shares more similarities with the music of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki or Arvo Pärt.

Passio et Mors Domini Nostri Iesu Christi Secundum Ioannem for 12 voices was written in 2012-2013, when Przybylski spent a year as composer-in-residence with the Solistenensemble Phoenix in Berlin. This composition, captured on record, has attracted critical attention not only in Poland:

Passio et Mors Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Ioannem (2013) for 12 voices, to give the work its full title, was presumably the main result of that residency and its a cappella style is closer to that of other relatively austere Passion settings – Arvo Pärt’s, for example – than to the overtly dramatic idiom of James MacMillan’s St John Passion (2008) for solo baritone, larger and smaller choruses and orchestra. ‘Holy minimalism’ will not do as a label for Przybylski’s work, however. Although its atmosphere is ritualistically intense and it moves slowly, with only the rarest hints of animation, its harmony is too unstable to sink into stagnation and its use of several different languages also distances it from any more obviously liturgical precursors. The booklet-notes by conductor Timo Kreuser spell out the music’s modal construction, explaining its rootedness as well as its ability to deal in predominantly dissonant sonorities and canonic manoeuvres sustained to achieve a hypnotically restrained effect. Some passages reinforce their meditative aura so determinedly that they risk an overly passive mode of expression; even the extended setting of the Stabat Mater seems more consolatory than mournful, and the music reaches out most powerfully to the listener when a more expressionistic quality is allowed to emerge. (Whittall, 2015)

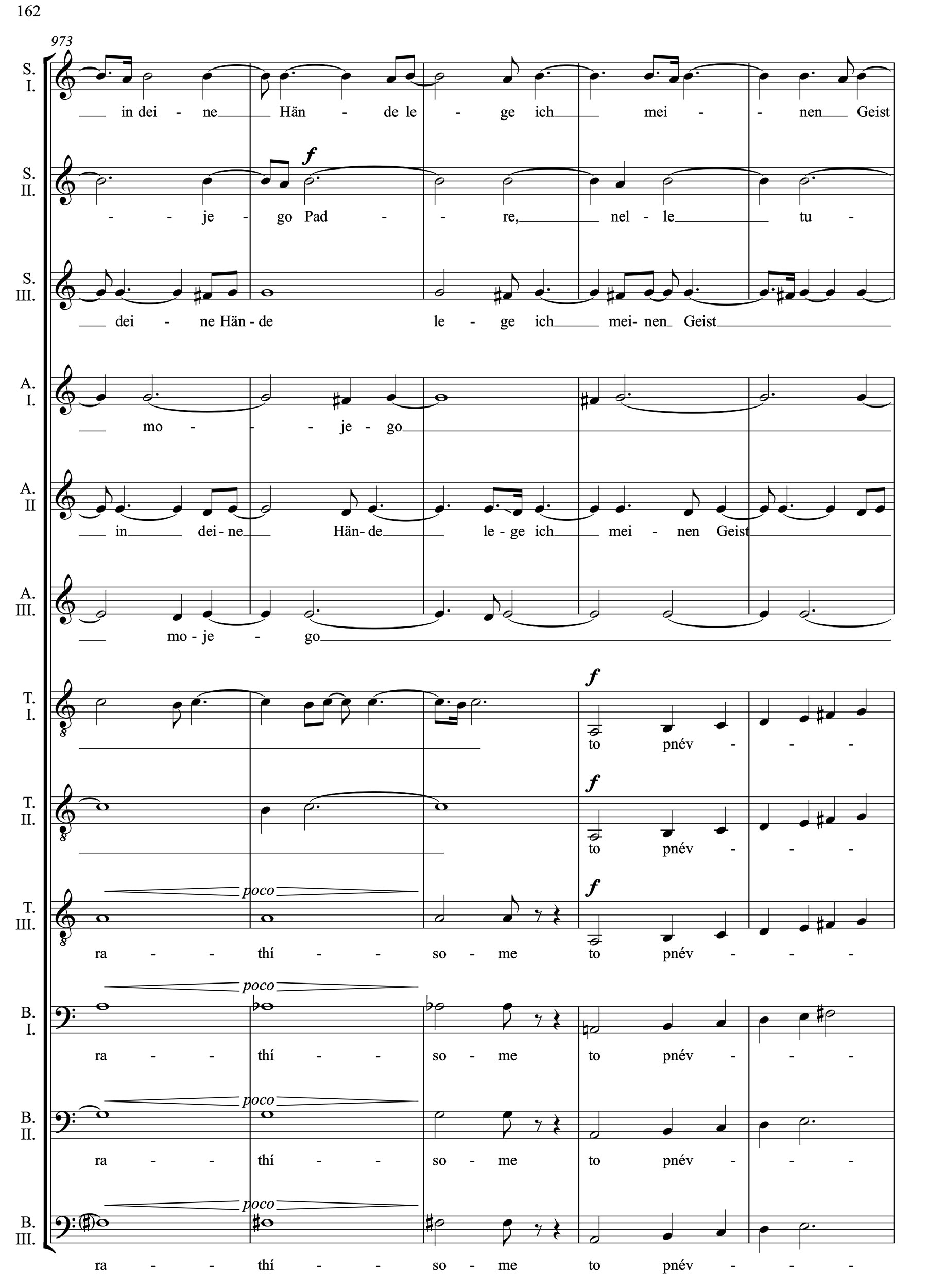

Example 1. Dariusz Przybylski, Passio, Septimum verbum

Example 2. Dariusz Przybylski, Orphée, Euridice’s aria, fragment

It’s possible that the mesmerising avoidance of straightforward melodic writing found in Ligeti’s choral works has left a trace in Przybylski’s music, coupled with a resistance to the forthright melodramatics of Penderecki’s St Luke Passion. Passio and the two shorter accompanying items seem almost obsessively concerned with constraining technical routines, yet the result is far from dull or monochrome and the performances are formidably accomplished. The recordings, made in Berlin’s St Thomas Aquinas Catholic Academy, have a degree of resonance that creates the illusion of voices turning into sustaining instruments – strings, brass – from time to time. That effect adds to the music’s persuasiveness, heightening one’s curiosity about the composer’s work in other media. (Whittall, 2015)

Another important field of Przybylski’s passéism is opera. The composer is very prolific and a number of his stage works have already been presented in professional theatres. Orphée is one of them (Przybylski’s operatic output also includes five chamber operas: Wasserstimmen, Manhattan Medea, Zwei Mäuse und ein Kater, Musical Land, Fall). The production of Orphée at the Warsaw Chamber Opera in December 2015, attracted much critical attention:

[…] Orphée, to a libretto co-written by the composer and the Lithuanian director Margo Zālīte, is ‘tragédie lyrique en musique’ but one should immediately add that is it a ‘tragédie en musique contemporaine’. The prolific Przybylski is well versed in the history of music and most skilful in the use of quotes and paraphrases, which is best exemplified in a mock chorale based simultaneously on the music of Gesualdo da Venosa and Olivier Messiaen. In Orphée one can hear many other influences but they add up to form a highly individual voice, with the large orchestra shimmering in radiant colours, brave brass interventions and an extended percussion group seated on stage. (Laskowski, 2016, pp. 472–473)

The libretto, written in French, is unfortunately the weakest element of this fascinating new work. It tells the well-known story of the mythic bard who goes to Hades to Example 2. Dariusz Przybylski, Orphée, Euridice’s aria, fragment bring his beloved Eurydice back to life. Przybylski and Zālīte decided to split the main character into four different personae – the Young Orpheus (Jan Jakub Monowid), the Adult Orpheus (Robert Gierlach), the Old Orpheus (Andrzej Klimczak), and the Alter Ego of Orpheus (proMODERN vocal ensemble supported by the accordionist Maciej Frąckiewicz; turning Orpheus into an accordion is a brilliant but somewhat cruel practical musical joke). Eurydice (Barbara Zamek) is not willing to go back to life, as her ex is too conceited and only interested in his own singing. Additionally, the characters of Apollo (Anna Radziejewska), a mysterious monk (Witold Żołądkiewicz) and Hermes (Mateusz Zajdel) appear in a Deus ex machina manner but they do not solve any problems. There are references to the four seasons, the seven deadly sins and Jacques Derrida, which results in a literary patchwork that is at times hard to follow. (Laskowski, 2016, pp. 472–473)

Yet another element of passéism in Przybylski’s work is his relationship with the concept of beauty, which – as Lipka writes when discussing Π [pi], Klavierstück I for piano and crotals from 2013 – cannot be discarded: Are you allowed to use the word beautiful when writing about new music’? Well, I dare say: this is a piece of rare beauty. I want to contain here the most modern sounding music in a truly traditional sense of the word. (Lipka, 2015, p. 10) Przybylski is also rooted in the past through his relationship (appreciation) of craftsmanship, which is clearly audible in his orchestration or use of solo instruments or the human voice. As the composer says while discussing his Cello concerto:

When I was composing it, I would bear in mind the whole heritage of the instrument from Bach’s suites, through perfect Haydn’s and Shostakovich’s concertos, up to Lachenmann’s total cello. (Lipka, 2016, p. 11) Contemporary classical music (newly written but not ‘new’ in the sense borrowed from Heinich) certainly has an audience and Przybylski is not alone in his quest to remain a composer of music rather than a creator/performer from the ‘l’art contemporain’ paradigm. He has certainly found an intellectual champion in Lipka:

[…] one could automatically infer the particular features of Dariusz Przybylski’s orchestral music. Przybylski is a composer who developed his own original and exceptionally appealing style considerably early. Nevertheless, on the whole, it is worth mentioning at least a few of this music’s features that make it so individual. First of all, it is noteworthy that the composer with such brilliant technique, which undoubtedly behooves him to create autonomous works, does not demonstrate the typical for our times fear of interweaving beyond musical threads into the tissue of his compositions. Moreover, he can do it subtly, with a dose of humour and distance, as if he were playing with the expensive possibilities of such a complex structure as an orchestra, which only a master could weave. The indisputable emotionalism of these works is always held under control of intellect. […] This is exactly at what Dariusz Przybylski excels: the excess of his ideas is always submitted to the general concept of form and its superior requirements. (Lipka, 2016, p. 15)

Now Dariusz Przybylski needs a champion who is a well-established practitioner that will take his music onto the most important concert platforms in the world. Given the quality of Przybylski’s passéist music that is not unlikely provided that the concert platforms will survive in a world that changes much more quickly than musical aesthetics.

Translated by Aleksander Laskowski

- ZEIT: What spaces does the so-called new music need?

Rihm: Actually it does not need any of those, where it would be sealed off as the ‘so-called New Music’. - Importance des discours (description, récit, interprétation), rôle primordial des spécialistes en position d’intermédiaire entre les oeuvres et le public, nécessité de la présence de l’artiste pour l’accès à l’oeuvre; diversification des matériaux, disparition de la peinture encadrée et de la sculpture sur socle, caractère souvent insatisfaisant des reproductions, prégnance de la valeur de singularité, jeu avec les frontières, crédit accordé à toute forme de mise à distance, effacement du critère de beauté; liens étroits entre acteurs du marché privé (galeristes, collectionneurs) et acteurs des institutions publiques (conservateurs de musée, commissaires d’exposition, directeurs de centre d’art); internationalisation des échanges, raccourcissement des délais de reconnaissance.

- […] d’une part, le privilège accordé à l’originalité plutôt qu’au respect des conventions, ou à la singularité plutôt qu’à la conformité aux traditions; et d’autre part, le déplacement du regard, des oeuvres à la personne ou aux attitudes de l’artiste, de sorte que le travail de singularisation opéré par les artistes sur leur propre personne devient partie prenante de leur oeuvre, comme en témoigne la régularité des efforts ainsi déployés. C’est toute une culture de l’art contemporain qui se construit et se transmet ainsi par les récits d’excentricités – par les anecdotes.

- Considérer l’art contemporain non plus comme une catégorie chronologique (une certain période de l’histoire de l’art) mais comme une catégorie générique (une certaine définition de la pratique artistique) me semblait avoir l’avantage de permettre une certaine tolérance à son égard. Car de même qu’on admet volontiers le droit à l’existence simultanée de plusieurs genres, même hiérarchisés, dans la peinture classique (peinture d’histoire, portait, paysage, etc.), de même l’on devrait tolérer l’existence simultanée, dans le monde actuel, de l’art contemporain et de l’art moderne, voire de l’art classique, même si celui-ci n’a plus guère de praticiens (mais encore beaucoup d’amateurs).

- Évaluation de la qualité sur le marché de l’art contemporain. Le cas des jeunes artistes envoied’insertion, a PhD Thesis written under the supervision of François Eymard-Duvernay, Université Paris-X, Nanterre, 2005.

- [...] si l’on soumet ces résultats à une analyse factorielle des correspondances, en distinguant sur un premier axe ‘la manièredont on considère les oeuvres’ (‘production’ ou ‘expression’), et sur un second axe la valeur principale selon laquelle on les juge (‘singularité’ ou ‘beauté’), l’on constate une opposition marquéeentre la classe correspondant à l’art contemporain – où l’art est considère comme une production et ou la valeur de singularité est primordiale – et la classe correspondant à l’art classique – ou l’art est considère comme une expression et ou prime la valeur de beauté. Quant àla classe correspondant à l’art moderne, elle partage avec l’une ‘la conception de l’art comme expression mais privilégie la singularité’ […]. Pour juger de la qualité des oeuvres. On ne peut mieux illustrer la situation intermédiaire de l’art moderne, entre art classique et art contemporain, non seulement sur le plan chronologique mais aussi sur le plan ontologique de la définition de l’art, et sur le plan axiologique de son évaluation.

- cf. Teatr Powszechny Website: http://www.powszechny.com/park-opera.html

References:

- Barrett, G. D. (2016). After sound. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Büning, E. (2013). Über die Linie. Wolfgang Rihm, ein deutscher Komponist. Vienna: Paul Zsolnay Verlag.

- Heinich, N. (1999). Pour en finir avec la querelle de l’art contemporain. Le Débat, 2, 106–115.

- Heinich, N. (2014). Le paradigme de l’art contemporain. Structures d’une revolution artistique. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Lipka, K. (2015). Con alcuna licenza [liner notes]. In Przybylski’s CD Album Songs and piano works. Warsaw: DUX.

- Lipka, K. (2016). The Unearthly aura of an infernal journey… and more [liner notes]. In Przybylski’s CD

- Album Musica in forma di rosa. Warsaw: DUX.

- Laskowski A., (2016). Opera Magazine, April 2016.

- Rihm, W. (2016). ‘Besser als Wagner’, an interview with Christine Lemke-Matwey. Die Zeit, 46. Teatr

- Powszechny Website: http://www.powszechny.com/park-opera.html

- Whittall, A. (2015). PRZYBYLSKI Review of the CD Album Passio for 12 Voices. Gramophone. Retrieved

from https://www.gramophone.co.uk/review/przybylski-passio-for-12-voices